The Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by the Government of Nepal (GoN) with China Gezhouba Water & Power (Group) Co Ltd (CGGC) seven months ago to develop the 1,200-megawatt Budhigandaki Hydropower Project has come under controversy from day one. The project is a storage project that promises to provide the much-needed hydro-electricity to solve the perennial power crisis in Nepal.

The MoU signed on May 4, 2017 paves the way for further formal agreement/s on the planning and implementation of the project. While the project development agreement/s based on the MoU are yet to be inked, the Government is expected to do serious homework about the details and the course to be pursued by the project in the future. Some discussion was undertaken about this project in the Cabinet on May 23, 2017 as well. At that time as well, the intention of the government to hand over the construction contract of the Budhigandaki project to CGGC was clearly ventilated. The project has been in the Government’s considerations for the last four decades. However, the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for the storage project was completed only in 2015. It did not take any position on the development modality for the project at that time. A resettlement plan for families that would be displaced by the reservoir to be constructed in due course had also not taken any shape at that time. The project was estimated to cost USD 2.59 billion, including the cost of land acquisition for storage purposes.

Janardan Sharma, the Minister for Energy signed the MoU with the Chinese company to build the project under the Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Finance (EPC & F) model. The project site is located between Gorkha and Dhading districts, and once constructed, it will be the largest hydropower project in the country as well as the largest storage project ever. The MoU was signed by President Lv Zexiang on behalf of CGGC at the residence and in the presence of Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and the Chinese Ambassador to Nepal, Ms Yu Hong.

Under EPC & F model, the Chinese company will help arrange funding to develop the project and undertake the overall responsibility for executing it. Finances will be mobilized in the form of soft or commercial loans from Chinese financial institutions under terms and conditions acceptable to the Government of Nepal. The MoU sets forth the modality for the exercise of this power.

The objective of this paper is to summarize the legal issues surrounding the project and draw a general conclusion on the state of affairs in this regard. It concludes that all controversies regarding the Budhigandaki project could be reasonably resolved, and it could still be implemented as an exemplary power project within the MoU framework, building on the trust that led to .

Features of the MOU

The CGGC, which is renowned for construction in the areas of power plants, dams, roads, bridges and civil engineering, and has invested and constructed highways; developed real estate; generated hydropower; and manufactured cement and civil explosives, has agreed to carry out the following activities under Article 4 of the MoU:

- Facilitate and arrange required financing (soft loan/commercial loan or any other means mutually discussed and agreed upon) from Chinese financial institutions on the terms and conditions acceptable to GoN;

- Assist GoN in the development and execution of the Project and undertake the overall responsibility of an executor of the project;

- Perform and execute additional studies and investigations if required by CGGC;

- Agree to work together with GoN in good faith, through joint and concerted cooperation in accordance with the provisions of this MOU, in order to implement the project on time;

- Cooperate and collaborate with Chinese financial institutions to design an appropriate financing structure for the project with the GoN’s assistance where permitting Chinese financial institutions, representatives to visit the Project site, and CGGC will bear the cost and fees as required, on their own;

- Execute the Project on the EPC & F basis with an appropriate contract mode under the agreed contract arrangement once the financial requirement is acquired through soft/commercial loan or any other means mutually discussed and agreed upon between and among the concerning parties;

- Ensure that all the procurement process during the project development period will be done in a competitive and transparent manner; and

- Suggest or intimate related information regarding the progress of work under this MoU to GoN in quarterly basis or earlier as the case may be.

Under Article 5, the MoU provides for a Steering Committee of ten representatives – five from each MoU party. The Committee will ensure the proper implementation of the MoU and will evaluate and determine the priority areas to successfully carry out the project works and possible financial structures for its timely implementation. Once constituted, the Committee will have to meet at least once in a two month time.

Additionally, one principal feature of the MOU is that it does not allow any party for the duration of the MOU work with any other third party in pursuit of a contract agreement for the project.

Any party may terminate this MOU, with reason, at any time, by giving thirty days written notice to the other party.

Finally, it is boldly accepted by Article 6.3 that the implementation of the project and related contractual arrangements will depend on the availability of required financial resources.

Belt and Road Initiative

Meanwhile, on the recommendation of the Nepalese side, China has listed the Budhigandaki Hydropower Project as one of the projects to be taken under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).1 Nepal signed a MoU with China to this effect on May 12, 2017, four years after the Intiative was launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping as part of his ambitious plan to expand links between Asia, Africa, Europe and beyond through billions of dollars in infrastructure investment. BRI is a priority for Nepal as well. The reason is – it has possibilities for Nepal to open up to the world through the Chinese territories, and easy funding for the infrastructure projects. The volume of the soft loan to be taken for the project is expected to increase following its inclusion in the BRI, which has strong backing of the Chinese government.

Nepal’s energy compulsions

Budhigandaki comes with certain clear possibilities. Energy crisis and heavy load

shedding has been a regular problem in Nepal for many years. This owes to lack of investment in energy sector, and limited growth in what has already been invested in this area. The problem became intense when neighboring India imposed an undeclared blockade in 2015, creating supply shortages of cooking gas and petroleum products, in the aftermath of the promulgation of the new Constitution of Nepal. The blockade was India’s response to the supposed failure of the new Constitution to respond to India’s demands communicated to the GoN diplomatically on the issue of constitutional reform. Given the two large earthquakes and the subsequent aftershocks that Nepal faced right before the blockade in early 2015, the effect of the blockade on India locked Nepal’s economy was enormous.

As a landlocked nation, Nepal imports all of its petroleum supplies from neighboring India. Moreover, India had also stopped Nepalese trucks at the Kolkata harbor, Nepal’s principle transit and trade point with India. The blockade choked imports of not only petroleum but also medicines and earthquake relief material. The blockade caused Nepal’s only international airport, Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu, to deny foreign carriers fuel, contributing to further isolation from the outside world and worsening the effects of the ongoing landslides blocking border trade with China. Nearly all sectors of the economy had taken a severe hit, from tourism to transport to domestic factories to agriculture and construction industry. The tactics of blockade is a regular feature of Indian diplomacy in Nepal.

In March 2016, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, who led the country in difficult days, signed 10 separate agreements with China, including the trade and transit treaty that ensured Nepal’s right to access sea as a landlocked nation through the Chinese land. Nepal had never sought this access through Chinese territory before. Thirteen months later, on May 12, 2017, Nepal and China signed the MoU on the Belt and Road Initiative.

Nepal understands that two reservoir projects – Budhigandaki and West Seti are important to meet Nepalese energy crisis. They also particularly help addressing the gap in energy supply between dry months and wet months. In January 2017, Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) and China Three Gorges Corporation (CTGC) put the initials on a joint venture (JV) agreement to build West Seti Hydropower Project. The government had handed over the project to it in 2012. The Budhigandaki comes as a second major project.

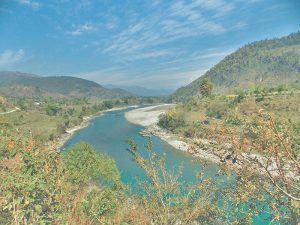

Budhigandaki Project Location and Catchment Area

The project site lies in the adjoining parts of Dhading district of Province No 3 and Gorkha district of Province Number 4. The project site is accessible through Benighat (at about a distance of 80 km from Kathmandu) on Prithvi Highway from Kathmandu to Pokhara. From Benighat, a motorable composite bridge can be used to cross the Trishuli River and access the Dam and Powerhouse site both of which are at a distance of about 1.5 km from the road head.

|

Catchment Area |

Dam site |

Dam site |

|

Gorkha: 2,700 km2 |

About 2 km u/s of the |

Ghyalchok (Gorkha) |

The salient features of the project have been summarized for the public at the official website of the project.2

Earlier efforts

Until recently, the Government thought of developing the Budhigandaki Hydropower Project in a ‘company model’, in place of its development committee modality accepted later. It was argued that the company modality will be more efficient, independent, and less susceptible to influence from political intervention.3 Ultimately, however, the development committee approach was chosen. The MoU signed with CGGC, which gives new possibilities, have already been noted above.

Land Expropriation

Land expropriation and compensation is a major issue in the Budhigandaki undertaking. The project is presently acquiring land in the catchment area of Dhading and Gorkha districts. The district administration offices of Dhading and Gorkha are currently extending compensation to owners of the land required for the construction of the project. Around 58,000 ropanies of land need to be acquired for this purpose. The number of the affected households are said to be more than 8,000. The reservoir of the storage project will submerge 3,560 houses and the occupants will need to be resettled with proper compensation. Likewise, 4,557 households will be partially affected by the project and need appropriate compensation.4

The government has given due priority to the Budhigandaki project in the budget for fiscal year 2017-18 as well, with allocation of Rs 10.17 billion for distribution of land compensation. The process has been rather slow, although all concerned stakeholders believe that it should be expedited.

Stakeholders’ claims

The stakeholoders of Budhigandaki have several concerns on the governmental initiative. Some stakeholders have clearly pointed out that the deal with CGGC has been reached without carrying out competitive bidding. The importance of bidding process in a huge project like this cannot be underscored. Surprisingly, though, contracts for projects below 100 MW capacity such as Kabeli A had been awarded only after carrying out competitive bidding in the past. This certainly has raised eyebrows in Nepal.

Some stakeholders have also questioned the Chinese company’s capacity to develop the project, given Budhigandaki’s enormity. The contract given to it to construct the 22 MW Chilime power project was abrogated after it completed only 10 per cent of works during the contract period in fiscal year 1997-98.5

In the fiscal year of 2012-13, the company landed the contract to carry out civil works of 42.5 MW Lower Sanjen hydropower project – a subsidiary of Chilime – but its performance was dismal. As a result, its security deposit was forfeited.6

Some think the EPCF MOU with CGGC is against the constitutional provision in Article 59 (5) of the Constitution, which ensures certain investment to the local communities in development of natural resources.

Agriculture and Water Resources Committee (AWRC)

The Budhigandaki Project has also been an issue at Agriculture and Water Resources Committee in the parliament.

The Parliamentary Committee on Agriculture and Water Resources has recently questioned why the decision to award the project to China Gezhouba Group Corporation was taken, going against the Committee’s past direction to build the project by utilizing domestic resources. Lawmakers also accused the government of handing over the national pride project to the Chinese firm without any competition and breaching the country’s public procurement laws. Earlier, after holding multiple discussions with Employees Provident Fund (EPF), Citizen’s Investment Trust (CIT) and Nepal Telecom (NT) as well as the project’s officials and experts, the house panel, had concluded that the mega project could be developed by utilizing domestic resources.

The validity of the decision has also been questioned stating that the agreement has been signed without getting it endorsed by the cabinet.

China Gezhouba Group Corporation (CGGC)

The concerns regarding CGGC must also be noted here. CGGC is currently building the 30MW Chameliya Hydropower Project in the far west and the 60MW Upper Trishuli 3A Hydropower Project in the central region in Nepal. The company could not construct both these projects in slated time. This raises the issue whether the CGGC can perform efficiently in the case of the Buddhigandaki.

CGGC has faced criticism time and again for inflating the cost of the project by citing various excuses and political hiccups. The construction cost of the Chameliya project has gone up to Rs 550 million per megawatt, while normally, the construction cost of a project is Rs 150 million to 200 million per megawatt. Moreover, the project, which was supposed to have concluded in May 2011, is yet to be completed.7 Nepal Electricity Authority has been bearing huge losses not only in terms of revenue but also due to increase in foreign exchange rate owing to the project construction delays, according to NEA officials. Besides, a case related to the company about tax evasion over fake VAT bill of over billion rupees is sub-judice at the Revenue Tribunal Office.8

A local newspaper has claimed that CGGC’s subsidiaries had been blacklisted by the World Bank on May 29, 2015. The World Bank’s move was based on ‘acknowledgement of misconduct by these entities in three World Bank-funded projects in China in relation to water conservation, earthquake recovery and flood management’. This meant that the company and its subsidiaries were ineligible to participate in any contract of the World Bank for 18 months. The claim has been refuted by the Company. It is said that the company had never landed in controversy. It is said that “CGGC is just one of the over 150 subsidiaries of China Energy Engineering Corporation (CEEC). It was some other subsidiary company of CEEC that had landed in controversy, not CGGC.”9

Press Release of Former Prime Minister

The Budhigandaki deal has come under criticism of former prime minister and coordinator of Naya Shakti Party Nepal Baburam Bhattarai as well. He criticised the government’s decision to award the construction contract for the Budhigandaki without a competitive bidding process.10 He emphasized that the government should build large infrastructural projects like Budhigandaki itself. His party has accused the government for signing the MoU with the company without formulating proper policies and executing directives on EPCF model. According to Om Astha Rai, “the fact that ex-Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai, viewed by many as pro-India, demanded the contract be scrapped fueled speculation that New Delhi indeed did not want the Chinese involved in such a large reservoir project upstream.”11

Issues that need to be addressed

Article 35 of Nepal Electricity Act 2049 states:

Government of Nepal may enter into contract for Generation, Transmission or Distribution of Electricity: Notwithstanding anything written elsewhere in this Act, Government of Nepal, by entering into a contract with any person or corporate body, may do or cause to do the generation, transmission or distribution of electricity subject to the terms and conditions as mentioned in such contract.

There is no doubt that Article 35 clearly gives power to the Government of Nepal to sign any contract with any person or body corporate for the purpose of generation, transmission or distribution of electricity. Its power to sign any MOU with China Gezhouba Water & Power (Group) Co Ltd (CGGC) is therefore legally sanctioned as long as the power is exercised in the interest of the country and without defeating the purpose of the law.

An open bidding process, had it been resorted to, may have given clear choice to the government in the matter of selection of the party, the cost of the project, the construction time, the amount of foreign currency involved and its interest, and also the overall national liability. The project cost of USD 2.59 billion itself is a huge issue. This amount is an estimated cost. According to Ratna Sansar Shrestha, a financial analyst in the energy sector, it obviously includes a handsome profit to the contractor, overhead expenditure, contingency expenditure as well as commissions that go to politicians, senior bureaucracy, brokers and so on. The real project cost will come up only after there is transparent competition between willing contractors.12 The signing of the MoU has certainly denied the people of Nepal an opportunity to see the transparency in the dealing.

As far as Nepal is concerned, there are already some good examples of projects completed in smaller amounts than the estimated amounts. For example, the hydropower project Kaligandaki – A had a declared estimated cost of USD 45 crore. It was completed using USD 35 crore. On the civil side, the project cost Rs 12,00,00,000 instead of the projected cost of Rs 7,00,00,000. Even with this variation, Kaligandaki – A was completed in less than the estimated amount. This means the real cost was 22 percent less than the projected cost. Similarly, while the estimated cost of Marshyangdi hydropower project was USD 32,33,00,000, the real cost was only USD 24,98,00,000. It was a difference of approximately 25 percent. The project was built by Nepal Electricity Authority itself.13

One additional example is Bhotekoshi Hydropower Project. It was carried out by the private sector. Its estimated cost was USD 10,00,00,000. Based on international competitive bidding, the contract was signed for USD 4,80,00,000 only. This amount is less by 52 percent of the estimated cost. This project was contracted out to CGGC. It is clear that estimated cost are liberally projected and there is always an effort to show high cost in order to work out an inflated power purchase agreement before the projected is kick started. It is thus clear that the Budhigandaki Project could not get the advantage of international competitive bidding process. It is thus the opinion of the financial analyst that the project could have possibly been contracted out for less than USD 200 billion had a transparent process been followed.14

Another issue involved here is the issue of cost increment. The MoU does not state anywhere what fixed cost the executor has to execute this project as proposed. This simply means that the regular cost increment is going to be the recurring feature of this project as well. A case in point is Mid-marshyangdi Hydropower Project. The project was contracted out for Rs 13,00,00,000. The contractor has already received Rs 27,00.00.000. It continues to claim further payment on various grounds. It is indeed clear that most of the projects operationalized by the Nepal Electricity Authority are based on inflated estimated cost. The main reason is the power contract management capacity of the NEA. The Kulekhani storage project is yet another case in point. Its estimated cost was USD 6,80,000. The real expenditure claimed was USD 12,36,000. Given this scenario, there is no reason why this situation does not repeat in the case of Budhigandaki. While the MOU does not fix the project cost, it does not give any clue as to how the cost will be maintained under certain standards. The more the cost increment, the more profit to the executor. It is the country which will have to bear the loss.15

Yet another startling issue about Budhigandaki is the project period. The MoU does not state by what deadline the project will have to be completed. The project delay is mostly a gain on the part of the contractor and loss on the part of the Government. The delay causes increase in the cost including additional interest in the project debt. If the project is late by one year, for example, the loss of electricity revenue will be 4,25,00,000 units. If the electricity tariff is fixed at Rs 5 per unit, the loss will be US 22,25,00,00,000. When Kulekhani was 21 month late, the Government lost USD 1,50,00,000. When Marshyangdi was late by 7 months, the country lost USD 1,7,00,000. When Kaligandaki A was 18 month late the loss was USD 10,00,00,000. In the case of Mid-marshyangdi, the delay of 50 months caused the loss of USD 13,00,00,000. Chilime was delayed by 40 months because of this same contractor. The fates of Chameliya and Trishuli which have still been struggling are still unsure. They are definitely causing huge losses to the Government.16

The financial management is yet another important issue. Under the MOU, the responsibility to garner necessary finance has been given to the contractor itself. While the contractor is a Chinese entity, the entities it is exploring for finance are also supposed to be Chinese. In that case – does this scenario affect the quality of negotiation? is an open question. The importance of financial arrangement under transparent conditions from the open financial market cannot be minimized. It has implications for interest rate. It is not clear how the government is going to check the unfair dealings between parties in the matter of loan negotiation and payment back period.

It appears that the loan lent out to Nepal will be in Chinese currency. Although there is no specific mention about this, since the financial entities will be Chinese, the currency released will be in Chinese. Nepalese currency is a weak currency. Even though the interest rate is so low, the principal amount itself is going to be always heavier. For example, 1 USD in 1995 was equivalent Rs 50. Now after 22 years the convertible rate is more than RS 100. In other words, had the Government taken USD 1 crore (i.e. 50,00,00,000) as a loan in 1995, and the amount remained unpaid, the principal amount now will be more than USD 100,00,000. The interest is quite an additional issue.17

As the project is to be worked out under the Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Finance (EPC & F) model, the project company will enter into a contract with the EPC & F contractor which will then enter into various subcontracts with its sub-contractors for performance of discrete portions of work. The EPC & F contractor provides the project company with a single point of responsibility to ensure that the project is completed on time and meets the performance requirements. The necessity of demanding a “performance guarantee” is therefore an important issue. In this type of contract, the contract price may be inflated as the EPC & F contractor is assuming most of the risk. Often there is limited ability of project company to be involved in the performance of the works. Inefficient use of resources is a possibility because there is no pooling of knowledge and skills. Risks may be placed on those unable to influence or manage them.

Conclusion

The MOU signed on 4 June 2017 is a skeleton document. As it is a skeleton, there is room for debate and also for doubts about the arrangement. Given Nepal’s experience with hydropower projects, the questions raised here, or the concerned expressed in this analysis, do not seem exaggerated.

One significant strength of the MoU is the provision in Article 5. The Steering Committee of ten representatives that it has created is based on the concept of joint management and collective decision making. The Committee has five representatives from each MoU party. It is the responsibility of the Committee to ensure that the MoU is properly implemented. It will also evaluate and determine the priority areas to successfully carry out the project works and possible financial structures for its timely implementation. This provision enables the Committee to create a win-win situation for both the parties.

All issues about law and finance as discussed above could be effectively handled by this joint management. Except the fact that the Budhigandaki project cannot be given to any other company under the existing arrangement, all other issues could be negotiated within the framework of the MoU and according to the recognized legal and business principles. For example, the MoU does not obstruct the joint management to work out a feasible range of investment opportunities to the locals, or the other Nepalese people. There is no reason why Article 59(2) cannot be implemented. Similarly, the Committee may also effectively help implement the public procurement laws that apply as there is a clear provision in the MoU to this effect. This is not a major issue. What is more important is to make the best use of joint management created under the MoU. This is a unique way to make sure that the project creates a win win situation for both the parties.

Again, the Budhigandaki project is a remarkable case. One must keep in mind that both the governments of Nepal and China have undertaken this project because of their understanding with each other, the ongoing energy crisis in Nepal, and a clear effort to establish a model for their future investments in Nepal (despite existing issues in the projects with Chinese companies). The Nepalese drive to seek reliable solution to the energy crisis in the country, and excessive dependence on Indian supply, and the Chinese willingness to establish itself as a dependable business partner in Nepal’s development, both demonstrate the move towards a new scenario. It is now their responsibility to make it happen.

All complications that have been discussed must be solved. The MOU does not deal with any of these complications, but it does not constrain fair and efficient, yet mutually agreed arrangement to work out this MoU. There is a room for model project arrangement even now. As far as China Gezhouba Water & Power (Group) Co Ltd (CGGC) is concerned, it is important that it completes all its projects in Nepal before giving hope to the Nepalese stakeholders that Budhigandaki is going to be different as far as its efficiency is concerned. There is also a media note that “CGGC seems desperate to rebrand its image in Nepal, and there is hope in some quarters that the company will deliver this time because the Chinese government is also keen to see this project completed in eight years.”18

This positive note notwithstanding, a petition has already been filed at the Supreme Court seeking termination of the MOU. The Company is waiting for the court verdict before starting the project.

1See “Project selection for BRI funding goes on” in The Kathmandu Post, September 11, 2017 available at http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2017-09-11/project-selection-for-bri-funding-goes-on.html

2http://www.bghep.gov.np/salient-features.php

3See “‘Company model’ for Budhigandaki Hydropower project: Energy Minister” in Republica, October 4, 2016.

4http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/news/2017-04-16/dhading-locals-finally-receive-compensation.html

5See “CGGC contract for Budhigandaki in controversy” in The Himalayanm Times, May 31, 2017

6See “CGGC contract for Budhigandaki in controversy” in The Himalayanm Times, May 31, 2017

7See “CGGC contract for Budhigandaki in controversy” in The Himalayanm Times, May 31, 2017

8See “CGGC contract for Budhigandaki in controversy” in The Himalayanm Times, May 31, 2017

9See “CGGC contract for Budhigandaki in controversy” in The Himalayanm Times, May 31, 2017

10See “No-bid contract flays award draws flak,” in The Kathmandu Post, June 9, 2017. Available at http://kathmandupost.ekantipur.com/printedition/news/2017-06-09/no-bid-contract-award-draws-flak.html

11“Reservoirs of suspicion Nepal is blessed with water resources, but cursed by geopolitics” in Nepali Times, 20-26 October 2017 available at http://nepalitimes.com/article/nation/reservoirs-of-suspicion/hydropower-geopolitics%20,3991

12See Ratna Sansar Shrestha, “Budhigandaki – Kalankit Rastriya Gaurav” in Nagarik Daily, Bhadau 6, 2074. Available at http://www.ratnasansar.com

13Ibid

14See Ratna Sansar Shrestha, “Budhigandaki – Kalankit Rastriya Gaurav” in Nagarik Daily, Bhadau 6, 2074. Available at http://www.ratnasansar.com

15Ibid

16Ibid

17Ibid

18See “Building Budhi Gandaki” in Nepali Times, August 6, 2017.

October 2017

Lecture Notes: Masters by Research in Energy and Infrastructure Law

Kathmandu University