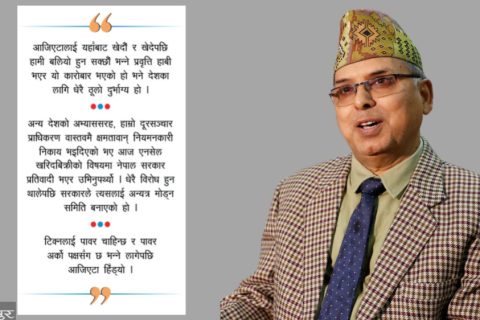

Nepal has completed the fourth year of its new constitution and has celebrated this with a lot of fanfare. While the government gave the Constitution Day (September 20) all emphasis it deserves, it is true that some political parties and civil society groups protested against the new Constitution while it was being promulgated in 2015. Some of them gave the constitutional anniversary a cold response, and some observed the day of promulgation as a black day. The concern about the future of the Constitution of Nepal, 2015, the seventh constitution, has been open to discussion, given that Nepal bid goodbye to six written constitutions for various reasons, internal and external, in the span of 65 years. On this occasion, Spotlight spoke with constitutional expert Dr Bipin Adhikari, who is also a senior lawyer of Nepal, about the issues surrounding the new constitution and its development.

The Constitution of Nepal, adopted in 2015, has now entered the fifth year. How do you comment on the Constitution and the status of its implementation?

Yes, the Constitution is four years old now. It is a democratic constitution, created by the elected constituent assembly, and is based on modern liberal institutions, including the three tier federal form of governance, secularism, pluralism, inclusion and accountability of state functionaries. It has been implemented from day one.

Most significantly, this has meant that elections at all levels of government and the formation of local, provincial and federal governments has changed the political landscape of Nepal. All 761 governments in the three tier system have begun operating. The process of implementation of the Constitution has also picked up, and most of the energy of the country has been spent on transforming the state.

What gives you the basis to say that the process of implementation has picked up?

The Constitution by itself was not enough. Elections were needed. Following the elections, it was necessary to create laws and institutions in order to implement the Constitution. Over the last four years, the Legislature Parliament that the new Constitution inherited has passed 87 new and amendment bills. The federal parliament that was elected under the Constitution has passed 43 new and amendment bills, which means that altogether, the country has now 130 statutes as required by the Constitution. Eighteen bills cleared by both the Houses are being sent for the presidential assent presently. All provincial and local governments were provided with necessary model laws to allow them the space for revision and adapting to local conditions before enacting these laws. Such developments have implemented the new Constitution and helped with Nepal’s federalization as charted out by the Constitution.

Critics point out that there is no progress in the federalization process despite these new laws. What is your assessment of the situation?

The claim is exaggerated. Federalization is a complex road map for a country with limited skills and competencies. And management of fiscal federalism is always a tough task. However, it is wrong to say that there has been no progress. Although the process has been slow, there is not only visible progress; the country has also started to move forward with the collective efforts of the governments at all tiers. The federal system is at work. Even now, there are more than two dozen bills in the houses of parliament at different stages of the legislative process. If the committees in federal parliament work sincerely, the bills could be cleared in the winter session when they have more time for legislative business. This will further consolidate the federalization situation. These laws must be implemented in order to progress further.

Some bills have been controversial?

Yes, some bills have been identified as adversely affecting the constitutionally-guaranteed fundamental rights and parameters of federalism. For example, the bill providing for regulation of relationship between the federation, provinces and local levels has been criticized for excess regulations, including the provisions of a national coordination council. The forest bill has ignored the fact that forest management is now a provincial issue. The National Human Rights Commission (first Amendment) Act tried to reduce the constitutional power of the human rights body. The Land Act Eighth Amendment Bill has been described as facilitating organized corruption and has generated well-known controversies. The government had to withdraw the Guthi Bill as a response to the people protesting against some of its provisions. The Media Council Bill became controversial for creating a council that has more decision makers from the government than the media itself, raising eyebrows of all concerned.

What are the reasons behind these lapses then?

There could be many reasons. Many of these lapses arise because there is little provision for consultation with independent experts and stakeholders. The Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs is adamant on a closed legal drafting process. The worry of the federal government that the provinces and local governments might become unruly is pervasive. There is a tendency of sprawling control and supervision in most of the statutes that should have promoted autonomy and self-government. Instead of being supportive, the federal government remains resentful about provincial and local autonomy in some key areas, like finance and development infrastructure. The bureaucracy is always interested in retaining power that has now been constitutionally transferred into the hands of the provincial and local levels. These aberrations need to be checked by the leadership.

What about local governments?

The Local Government Operations Act has been a milestone, although it also needs some reforms based on our experience in the last two years. Local democracy has become a reality in Nepal in the executive and legislative spheres, and Judicial Committees have been functional throughout the country, as are judicial arms for some carefully enlisted grassroots causes. The federal government assisted lawmaking at local level by supplying the necessary model laws, rules, procedures and even directives. Similar support was provided to the provincial governments as well. They have started working in the area of policy-making, and their channels and connections with the federal government have also been established. Now, the emphasis should be on good governance and the end of corruption.

Some people, even experts, are of the opinion that the three-tier federalism is an overstatement of the federal system in Nepal and should have been avoided. How do you respond?

I do not agree. It is a very good system that embodies innovative thoughts. It clearly emphasizes on grassroots democracy. At the provincial level, the power of the provincial government should be strongly defended. The challenge is to boost provinces and remove overlaps in the division of power between the federation, provinces and local governments. In particular, there should be clear legal norms as to the use of concurrent power by the respective government. As we are in the beginning phases of implementation, it is natural that the federal government takes leadership. But it should learn to stand with the constitutional spirit inherent in Article 232: coexistence, cooperation and coordination. Unfortunately, we have some irritations there.

Many critics think the local governments have become a local Petri dish for ever-increasing corruption in Nepal.

There have been reported cases of corruption. The federal government should help the local governments by training officers in accounting systems, procurement laws and compliance with economic and financial procedures. There have been problems of book keeping also. We should keep in mind that there have been some changes in the development scenario, and guidance is lacking from the federal government and provinces. There are changes in the modus operandi; it is not all corruption. The federal bureaucrats and the political branch as well have not been very cooperative in sorting out problems at the local level.

Does it mean that the federal government is becoming authoritarian?

Recently, authoritarianism is on the rise even in established democracies. People have to remain vigilant. In our case, I do not think authoritarianism helps the government, which has inherited many problems, in any significant way. Impeachment proceedings last year spoiled the image of the government. Parliamentary hearing has been a disaster.

Even in the area of federal, provincial and local relationships, the federation should seek cooperation rather than issue inappropriate orders. The alternative is to discuss the federation’s worries with the provinces or the local level and develop the necessary understanding. The committees in parliament should revive the culture of working as lawmakers rather than performing the role of a party proxy. They can develop the solutions if they forget which party they come from and concentrate on just and efficient solutions. Otherwise the regional and global scenarios will continue to haunt the Nepalese as well.

What about the Supreme Court Constitutional Bench? Is it functional?

Yes, it is trying to function. It has received 389 petitions of which only 215 have been finally decided. This is the figure of September 17. This means that the case disposal rate is low, and the federalization process has not received the necessary inputs from the Constitutional Bench. These inputs would have helped the governments at all levels, as these cases involve issues of unconstitutionality of federal statutes, provincial laws, local governments and electoral affairs.

What is affecting its efficiency in that case?

There must be many reasons. The Constitutional Bench was created as a compromise formula for judicial settlement of federal disputes between constitution-makers who wanted a European style of Constitutional Court, and others who did not want the power of the Supreme Court to be stripped off. It was possible to design and develop the Constitutional Bench in the model of the constitutional court within the existing Supreme Court parameters. But no such effort was made. In its present form, it is more of a problem than a solution.

Why it is more a problem than a solution?

My opinion is that the Supreme Court can go ahead as a federal dispute settlement mechanism even without creating a structure like the Constitutional Bench. But if the Bench has been created, as it was discussed during the constitution-making process, it should have been able to work as a full-fledged constitutional court within the Supreme Court and the integrated judicial system to meet Nepal’s federal requirements. So far, this has not happened because the Supreme Court Act and Rules were revised without looking into the federal requirements. So the provision of the Constitutional Bench does not add any value to the requirements of the change.

What are these federal requirements?

They require expert judges with clear background and knowledge in federalism. It should have been inclusive for different provinces, ethnic compositions and gender orientations. There could be more roles for external experts and practitioners as demanded by the subject matter of the dispute. The lawyer-induced outcome alone does not always help decision-making at this level. The procedures for judicial decision-making could also be more flexible and based on stakeholder hearings, among other factors. A firm delimitation of power between the functions of the constitutional bench and that of the Supreme Court is necessary.

There is a claim that the statutes created for the implementation of fundamental rights have not been immediately enforceable and adequate. Is it true?

As far as economic, social and cultural rights are concerned, the statutes passed last year have not been adequate. Some of them require the enactment of additional rules in order to make them enforceable. It is important that the government initiates discussions on how to implement Article 42 of the Constitution. This is necessary to implement the fundamental right to proportional inclusion in the structure of the state. This is important for women, dalits, janajatis, madhesis and others, who have not been adequately represented in the state system and especially in the civil judicial and military services of the country. Therefore, there is a flaw in the governmental approach.

What is the status then of the formation of autonomous regions?

Not much has been done so far. The Local Government Operations Act 2010 has legal provisions regarding this matter, but they do not capture the essence of these special arrangements. They are very important for indigenous people as well as the local economy, which have been waiting for the break. We also need to ensure that the language, religion, culture, and habitat of indigenous people are maintained. It is possible to declare all 17 Himalayan districts of Nepal as special autonomous regions within the existing constitutional norms and with minor amendments to the Local Government Operations Act 2010.

Are District Coordination Committees necessary?

It could definitely have been avoided by the framers of the constitution. Some leaders of the dominant political parties wanted the administrative districts to continue in Nepal but were not clear about how to do it. So they gave some coordination powers to these committees as far as the village bodies and municipalities in their district were concerned. Ideally, it was not necessary. The provincial governments exist for this purpose when necessary. However, they have been created and established. Their utility will be proven if they create value for themselves in the present scenario, especially the within the three tier federal system, in which they have been placed under the third tier.

What is your opinion on the many appointments of the government that have been controversial?

We have a system where party affiliation is important than the quality, competencies and character of candidates. Be it judicial appointments or constitutional appointments of other types, the best in the country have not received the offers. Instead, vested interests have their influence in the selection process. This is the biggest challenge in Nepal in recent years.

The role of the Public Service Commission in the recent hiring process has also been criticized by some. What do you think of it?

I also think the Commission could have advised the government to revise the law in the constitutional spirit rather than accommodating a recommendation that has been issued that affects federal parameters. Hiring more than 9,000 civil servants was a huge opportunity to induct women, dalits, janajatis, madhesis and minorities in the state structures. Or the Commission should have asked the federal government to help pass the law and expedite establishing the provincial public service commissions which should have advertised provincial positions on the recommendation of the provincial government. Moreover, Article 42(1) of the Constitution gives such communities the right to proportional inclusion in the state. Therefore, this move was constitutionally incorrect.

How do you see the role of the opposition in defending the Constitution?

The opposition of Nepali Congress in particular looks fragile. It is not moving because it has lost its moorings: the teachings of B. P. Koirala. It has immense potential, but the leadership problem is a vital one. The government does not have the critical back up, because the opposition is also disillusioned. It needs to defend the Constitution promulgated under its leadership.

What about the prospect of the constitutional amendment?

The first question is what is the constitutional amendment for? Do we want secularism to be withdrawn? Is there a case for the restoration of monarchy? Do we want the country’s federal features to be scrapped? Should we re-divide the country based on ethnic territories? There is a lobby for all these fronts. It is important that we do not axe on the steam of the Constitution.

Again, there are others who want a reform in the electoral system, the name and number of provinces, citizenship provisions and even the change in the form of government from a parliamentary to a presidential one. We cannot satisfy all voices, even if we want to give everything to every political party.

The government should work with stakeholders to look into the proposal for amendment and seek compromise solutions. It is important for the parties also to go to the people and garner necessary votes to move on amendment proposals of the people’s choice. Should that not be the course in a democracy?

Is there any possibility of constitutional backlash in Nepal?

There is no possibility of a constitutional backlash in Nepal. I do not see it. If geo-political elements become active, I cannot say, because they have the tendency to shatter order in Nepal.

In other cases, the new constitution is the story of a modern Nepal. Implement it in its true spirit, and it will open up to accommodate more and more dissenters. You need institutions that are equipped, efficient and committed to do so. Weak institutions can neither give strong results nor fulfill constitutional aspirations.