The AIIB follows a six-step process for the approval and completion of projects in Asia. These are as follows: strategic programming, project identification, project preparation, Board approval, project implementation, and project completion and evaluation. All powers of the AIIB are vested in the Board of Governors. Typically, the AIIB’s long term repayment includes a five-year grace period and an interest rate of 1 to 1.5 percent.

The China-pioneered Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the first international institution created by a non-western power, has at once become relevant to Nepal and its multifarious investment needs. While the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the two international institutions established after World War II, remain active with the support of the US and the western countries, the global economic system will not remain the same after the emergence of the AIIB. Whether the new entity is taking shape and promising a change that many developing countries have been looking for is still open to question.

Nepal’s investment scenario has not changed qualitatively as far as investments in major infrastructures are concerned. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Government of Nepal has encouraged foreign direct investment (FDI) in many sectors, including land and food production, hydropower and infrastructure development, and the tourism sectors. And the results have been quite satisfactory; according to World Bank’s Open Data, FDI inflows into Nepal as a percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) was at its historical in 2017 at 0.789. By comparison, the same number for Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and India is 1.574, 0.923, and 1.537, respectively. For a country emerging from the lasting effects of a civil war, the number is quite impressive. Yet, it is not enough.

What is being sought is also a big push. In development and welfare economics, this means that a stagnant economy requires a “big push,” a large wave of minimum investments as opposed to a sprinkle of investments, to move towards higher levels of productivity and growth of income in the economy. For Nepal, even as it secures funding from several foreign investors for large-scale infrastructural projects, this big push has not been a reality thus far. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific is of the position that “[t]he provision of adequate infrastructure, along with macroeconomic stability and a long-term development strategy, is one of the necessary conditions for sustainable economic and social development.” The opinion is certainly correct.

What is being sought is also a big push. In development and welfare economics, this means that a stagnant economy requires a “big push,” a large wave of minimum investments as opposed to a sprinkle of investments, to move towards higher levels of productivity and growth of income in the economy. For Nepal, even as it secures funding from several foreign investors for large-scale infrastructural projects, this big push has not been a reality thus far. The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific is of the position that “[t]he provision of adequate infrastructure, along with macroeconomic stability and a long-term development strategy, is one of the necessary conditions for sustainable economic and social development.” The opinion is certainly correct.

A study, for example, finds that China’s prosperity can be partly attributed to investment-led growth, and that particularly, “[i]Infrastructure development in China has significant positive contribution to growth than both private and public investment.” Moreover, another study also finds that the differences between growth performances in various parts of China can be explained by “geographical location and infrastructure endowment … The results indicate that transport facilities are a key differentiating factor in explaining the growth gap ….” Therefore, an important pointer for Nepal is that careful and deliberate investment is necessary for sustainable economic growth, especially with regards to connectivity and access.

The first ever infrastructure-targeted development bank of Nepal, the Nepal Infrastructure Bank (NIB) received its operating license in February 2019. The NIB is the first bank that is established as a public-private partnership, with the government and the public sector owning 10 and 90 percent, respectively. In a move to support the NIB, the Nepal Rastra Bank (Nepal’s central bank empowered to grant the license) has “allowed [the NIB] to issue loans up to 90 percent of its credit to core capital and domestic deposits ratio,” even though the regular limit is 80 percent. With a focus on infrastructural investment as well as “construction, transportation, agriculture, energy, tourism, special economic zone, urban development and information technology,” the NIB will have an authorized capital of Rs. 40 billion.

International Opportunities for Nepal

The AIIB, beginning operations in January 2016, is anticipated to be a major financial institution of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The AIIB is a multilateral development bank, headquartered in Beijing, with 93 approved members worldwide. A $100 billion bank, the AIIB’s main focus is investment in Asia to enhance social and economic outcomes. The AIIB is constituted and governed by public international law (thereby, international administrative law), including international conventions, customary international law, and general principles of law and the rule of law.

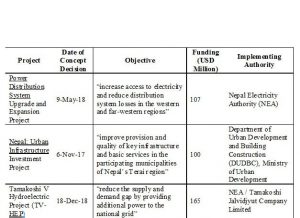

[Table 1 AIIB Projects Proposed in Nepal]

China (26.78 percent voting power), India (7.69 percent voting power), and Russia (6.05 percent voting power) are the three largest shareholders in the AIIB. Nepal joined the AIIB in January 13, 2016 and has a total subscription of USD 80.9 million and a voting power of 0.28 percent. Since its operation, the AIIB has proposed projects in Nepal as well, mainly in the energy and infrastructural sectors (see Table 1). These projects have yet to be approved. There is little doubt that Nepal has an equal opportunity as any other Asian country to continue to attract funding for potential infrastructural projects.

Trends of the AIIB

In the three years since its inception, according to John Hurley, a policy analyst, the AIIB demonstrates three key takeaways: it continues to attract funding from other multilateral development banks (like the WB), it co-finances with such banks, and it will finance projects in countries that other institutions have typically ignored (e.g. Russia and Iran). These trends demonstrate the AIIB’s commitment to diversifying funding and diluting risks for sustainable financing. Moreover, the Bank is available for every country.

In the three years since its inception, according to John Hurley, a policy analyst, the AIIB demonstrates three key takeaways: it continues to attract funding from other multilateral development banks (like the WB), it co-finances with such banks, and it will finance projects in countries that other institutions have typically ignored (e.g. Russia and Iran). These trends demonstrate the AIIB’s commitment to diversifying funding and diluting risks for sustainable financing. Moreover, the Bank is available for every country.

Despite these features, the AIIB draws some critiques as well, including the fact that China does not differentiate between democratic and undemocratic or oppressive regimes; therefore, it worries some that there is a possibility of AIIB’s funds going into the pockets of unaccountable authorities. Additionally, although under Article 13 of the Articles of Agreement, the legal document legitimizing the operations of the AIIB, it promises to ensure its projects uphold its policies regarding environmental and social impact, some scientists worry how large-scale transport and road projects, financed inappropriately, will degrade the surrounding wildlife and environment. Concerns regarding the displacement of local populations because of infrastructural investment and corruption are rampant as well. Additionally, some critics point out China’s obvious veto power over major decisions by the AIIB as it holds the highest voting power.

China’s response to these criticisms is notable as well. Joining Western powers in upholding the international norms and standards of sustainable financing has been well-regarded as China’s attempt to curb some of the criticisms about sustainability and environmental impact. This extends to concerns about human rights as well and the involvement of international and regional banks in ensuring that international standards of human rights are upheld. Additionally, some scholars emphasize that this China-led multilateral development bank complements the existence and policies of existing western banks and is not a confrontational force to the global financial governance system.

Bretton Woods and the AIIB

Before the AIIB came the Bretton Woods system, the first international monetary systems that aimed to create an efficient foreign exchange system (based on the U.S. dollar and the value of gold) and promote international economic growth. The Bretton Woods Agreement gave way to the establishment of the IMF and the WB. The IMF has been focused on promoting international monetary cooperation, while the WB has focused on lending to developing countries for economic growth.

It is important to consider how the IMF and WB differentiate from the AIIB. For starters, membership in the Bretton Woods system was largely composed of Western countries and Japan, an alliance continued after World War II of the Allied nations. The AIIB, on the other hand, did not form post-war, focusing on repairing the damages from the war and then moving on to developmental goals. Instead, the AIIB was founded on the idea of fostering economic activity through investment and offers membership to any and all countries, regardless of their economic status in the world, with allocated voting power. Additionally, the AIIB is not only for wealthier countries, and a study finds that actually countries that are underrepresented in the global financial arena are more likely to join.

It is important to consider how the IMF and WB differentiate from the AIIB. For starters, membership in the Bretton Woods system was largely composed of Western countries and Japan, an alliance continued after World War II of the Allied nations. The AIIB, on the other hand, did not form post-war, focusing on repairing the damages from the war and then moving on to developmental goals. Instead, the AIIB was founded on the idea of fostering economic activity through investment and offers membership to any and all countries, regardless of their economic status in the world, with allocated voting power. Additionally, the AIIB is not only for wealthier countries, and a study finds that actually countries that are underrepresented in the global financial arena are more likely to join.

Additionally, the AIIB and the western multilateral development banks differ in their ideologies. The western institutions followed a liberal economic theory to promote democracy around the world. Contrastingly, the AIIB is mostly removed from domestic matters of the borrowing countries; the Articles of Agreement explicitly bars members from influencing political affairs of borrower countries. Unlike the WB, the AIIB does not require privatization or deregulation for potential borrowing countries to qualify for funding. In a way, this is helpful to some countries that face issues convincing pre-existing financial institutions to extend investments.

Another important issue for Nepal will be how much ownership Nepal can take on to construct and maintain the projects. China and other lending institutions emphasize sovereignty of the borrowing countries to lead projects, make decisions about the countries’ needs, and establish policy frameworks to reap the benefits of infrastructural projects. However, the lack of conditionality in qualifying for loans means that it will be up to Nepal to improve both governance and policy to ensure success. It will be very important for Nepal to ensure a rigid policy framework and build the capacity of its human resources in order to avoid failed projects and the subsequent debt distress.

Legal issues pertaining to AIIB in Nepal

Maintaining international levels of environmental standards is one of AIIB’s commitments for all the projects it will fund. For example, some argue that the AIIB is not “rigorous in its evaluation of mitigation measures” and vague about issues of biodiversity. In the case of projects’ effects on natural habitats, the AIIB requires a cost-benefit analysis; however, the AIIB is unclear about how it will conduct such analyses, and the ultimate argument for the construction of a project may be arbitrary with a simple defense of the economic gains outweighing environmental protection. Upholding international environmental standards are especially important for Nepal, which is one of the most vulnerable countries to climate change.

In the area of labor standards as well, the AIIB is amendable to some international standards, although some scholars argue that it has fared poorly. For example, it explicitly prohibits forced labor and uses similar language that the International Finance Corporation, the private sector arm of the WB, uses. However, while the AIIB prohibits child labor through a Minimum Age Convention, it is not party to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention (to which the ICF is party), which leave open some loopholes. This includes child labor moving to unregulated sectors outside the specified industries under the Minimum Age Convention.

In Nepal, child labor is very much rampant, although it has been declining, and disproportionately hurts girls; additionally, 60 percent of child labor is engaged in hazardous work. The Government of Nepal has various initiatives (including the National Master Plan (2011-2020)) to curtail child labor. It’ll be important that such national and international standards are maintained in Nepal for AIIB-funded infrastructural projects, even when AIIB itself isn’t party to such standards.

The AIIB, together with the World Bank and other such institutions, presents a great opportunity for Nepal to seek funding for various infrastructural projects. The diversity of its funding and its members is a safety net for borrower countries like Nepal, as it provides for sustainability and a system of accountability. Moreover, infrastructure-related funding is crucial for Nepal, a country that contains various isolated areas lacking simple facilities. A September 2018 study by AidData, a research lab at College of William & Mary, finds that Chinese investments, especially in the transportation sector, reduce economic inequality within and between sub national localities. “Connective infrastructure,” they find, creates positive economic spillovers and equal distribution of economic activity in the implemented areas.

As a mechanism for accountability, the AIIB drafted and received comments and recommendations from international organizations concerned with project-effected people on its Project-Affected People’s Mechanism (PPM). These organizations, in a letter to the AIIB, raised concerns over the exclusions of the principles of accessibility, transparency, and legitimacy in the PPM. It also pointed out that only 12 of its initial 60 recommendations for best practices had been adopted by the AIIB as well as specified paragraphs in the draft that were deemed problematic. The writers of the recommendation pointed the “[u]nrealistic requirements to demonstrate ‘substantial’ harm,” “[u]nreasonable preconditions to filing submissions,” as well as a “[c]omplex and rigid filing system,” among other concerns. A comprehensible and smooth process will be necessary for borrowing countries and the people affected by infrastructural project, many of whom in Nepal would be isolated indigenous communities that depend on the surrounding forests, to ensure that projects will actually bring the prosperity that they promise.

Similarly, while international dispute resolution has been used by other multilateral development banks, scholars (Radavoi and Bian (2017)) emphasizing the influence of China in the AIIB argue that China generally is reluctant to pursue dispute settlement by third parties as a mechanism for resolution and instead opts for bilateral consultation or other non-compulsory mechanisms. However, the AIIB is multilateral and often collaborates with the WB, which emphasizes dispute resolution by a third party; additionally, the November 2018 AIIB conference focused specifically on legal dispute resolution, demonstrating that it will be an important factor for AIIB-funded projects.

Conclusion

The AIIB, together with the World Bank and other such institutions, presents a great opportunity for Nepal to seek funding for various infrastructural projects. The diversity of its funding and its members is a safety net for borrower countries like Nepal, as it provides for sustainability and a system of accountability. Moreover, infrastructure-related funding is crucial for Nepal, a country that contains various isolated areas lacking simple facilities. A September 2018 study by AidData, a research lab at College of William & Mary, finds that Chinese investments, especially in the transportation sector, reduce economic inequality within and between sub national localities. “Connective infrastructure,” they find, creates positive economic spillovers and equal distribution of economic activity in the implemented areas.

Because debt distress can become a major issue for countries with low GDP, it is important for Nepal to carefully evaluate the need and anticipated returns of its investments. The process of approval for AIIB funds ensures that Nepal has the mechanisms, including technical assistance, to make such decisions. Additionally, while infrastructure investment is crucial, so is the continued investment and support of “soft infrastructures,” namely, health policies, education, and management systems for administration, urbanization, and other such factors. It is essential that physical infrastructure development is accompanied by human capital formation as well in order to ensure sustainable economic growth. The complementary growth of Nepal’s infrastructures and human capital is necessary for Nepal to realize economic growth and prosperity.

[Dr Bipin Adhikari is a constitutional expert and is currently associated with the Kathmandu University School of Law. Bidushi Adhikari is associated with Nepal Consulting Lawyers, Inc as a research assistant.]