[Soaltee Crowne Plaza, Kathmandu]

Rt Hon’ble President Madam Bidya Devi Bhandari

Hon’ble Subas Chandra Nemwang, Chair of Constituent Assembly I & II

Dr Ram Sharan Mahat, Member CA I & II, and Former Minister

Dr Kamal Hossain, Constitutional Expert, Bangladesh

Professor M. P. Singh, Constitutional Expert, India,

Professor Qianfan Zhang, Constitutional Expert, China

Professor Suresh Raj Sharma, the Founding Vice Chancellor of Kathmandu University

Senior Advocate Daman Nath Dhungana, the Chairperson of Kathmandu University Trusteeship Council

Dr Ram Kantha Makaju Shrestha, VC, Kathmandu University

Distinguished guests

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is with great honor and privilege that we welcome each and every one of you to this Conference on the 2015 Constitution of Nepal on behalf of the Southasia Trust and Kathmandu University School of Law.

I heartily welcome our distinguished guests, from near and far, some of whom have journeyed long to join us here in Kathmandu to discuss an incredibly significant document in the history of Nepal.

Please allow me a moment to recognize the presence of the head of state the Right Honourable Bidya Devi Bhandari. Additionally, a special welcome to our international guests from more than a dozen countries who have joined us here today. And of course, we are grateful for the attendance of approximately 150 participants including panelists, commentators and presiding experts and practitioners.

Nepal has a new Constitution again. The document promulgated in 2015 is our latest effort to live with constitutional democracy and constitutionalism. It must be recalled that we had new constitutions in 1948, 1951, 1959, 1962, 1990 and 2007 as well. So, we are a country and people that have already tasted six constitutions in the span of 59 years; the 7th constitution was drafted over a span of approximately eight years. However, the 7th Constitution is distinct in several ways. To begin with, this is the first Constitution in Nepal built and adopted by an elected Constituent Assembly through a protracted political process. This is the first republican constitution. While these features add to the democratic credentials of the document, these changes must be understood in a larger political context.

The new Constitution builds on the consolidated parliamentary system of government at the federal and provincial levels. It now has additional features to ensure stability in the parliamentary leadership. A three-tier system of cooperative federalism has been worked out, that allows the local governments separate constitutional competences and safeguards. There is a 7-province model at work. The list of fundamental rights guaranteed to Nepali citizens has been revised again. Many socio-economic and cultural rights find a place of prominence in the Constitution. The directive principles and policies of the state, which explain the constitutional horizon of the change, although not enforceable at any court, will now be under the jurisdiction of the parliament. There are now parliamentary machinery and procedures that will monitor the efforts of the state to realize these constitutional commitments.

The right to proportional inclusion, that allows participation in the state structures to almost 16 groups of deprived and marginalized people, remains the vanguard of the new constitutional design. Many new constitutional commissions have been created to ensure protection to the people, who need extra care. There are efforts to ensure equality, identity and protection of sub-cultures. The state has become secular. The system of judiciary remains integrated for all levels, but the Constitution has created judicial committees of elected officials that allow them to exercise judicial power that is most relevant at the grassroots level. I will leave the further evaluations of these themes for the discussions in the next two days. All I want to emphasize here is that the nature of the state in Nepal is in the process of change, and this change, in the matter of executive, legislature and judiciary as well the rights of the people, will become qualitative as we focus our efforts in strengthening the regime with interaction with the most vulnerable and deprived communities. This calls for responsible and participative law making.

The 2015 Constitution of Nepal is a document of compromise of competing values, norms, standards and procedures. After over 67 years of challenges including great political upheavals, change of guard in the political leadership, continuing economic deprivation, a violent conflict of a decade, geopolitical pressures, and victimisation of the constitutional process, we have finally been handed a document that makes new promises to the people. It upholds the principles of equality, diversity and growth. Anyone who has read the 2015 Constitution will agree that it reflects and addresses the subtleties of the makeup of Nepali society, with its diversity in demography, culture and geography. Whichever way one looks at it, the promulgation of this Constitution was a significant event because it completes the peace process, closes the uncertainties regarding the political system and paves the way for future constitutional progress.

I believe that the life of a successful constitution, no matter how democratic and human rights-oriented it is, depends on its consistent and effective implementation as well as timely reforms based on new developments in the country. Only when we, as the people, are able to foster a progressive and forward-looking environment can a constitution truly evolve to reflect a society, its people and their challenges. Without such an environment for rigorous implementation, continuing reviews and engaged citizens, the constitution is, what Late Prime Minister B. P. Koirala said, only “a straw of corn,” after all. In other words, as Albert Einstein famously stated, “The strength of the Constitution lies entirely in the determination of each citizen to defend it. Only if every single citizen feels duty bound to do his share in this defense are the constitutional rights secure.”

This Conference gives us the opportunity to understand Nepal’s new Constitution, analyze its contents, look into it in the larger socio-economic and comparative context, and review the implementation challenges. It has been three years since the Constitution was promulgated; the implementation of many articles in the Constitution has been set in motion. The norms and standards defined by the Constitution have begun to materialize. Three years later, however, we still see new challenges unfolding, and we must stay open-minded and progressive if we are to truly make this Constitution a document of our time. I am sure our deliberations here will help us look backward and move ahead with renewed determination.

In spending the long but rewarding hours preparing for this Conference, I have hoped that it is productive and informational to all our attendees. Through the panels that we have organized for the next two days, I hope that we are able to exercise timely thoughts, analysis, and conclusions on various discussions topics, which span from the constitutional rule of law, checks and balances to the rights of marginalized to vulnerable communities, inclusion, federalization and many other important issues.

I expect that this Conference will achieve its objective of creating a pool of knowledge that will help the country and people move forward with renewed faith and determination.

Before I conclude I also want to thank First President Dr Ram Baran Yadav for kindly sending his written message to the organizers for the successful completion of this Conference.

Thank you once again for being here.

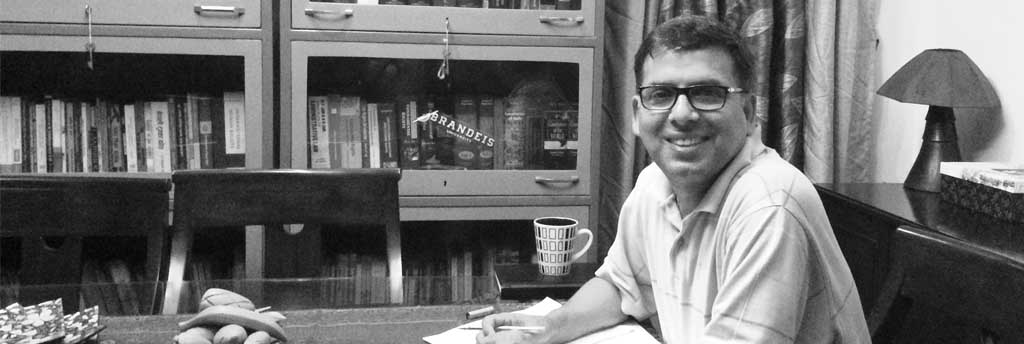

[Convenor Dr Bipin Adhikari introducing the Conference at the Launching of The Conference on the Constitution of Nepal, August 11, 2018]