February 19, 2011

With less than three and a half months to complete the unfinished task of constitution writing in Nepal, the level of political compromise between the country’s major political parties needed to get through the key issues is far from materializing. For this to happen, Nepal needs a government, which has the support of at least two-thirds of the members of the Constituent Assembly (CA). This alone can set the stage.

The newly elected Prime Minister Jhalnath Khanal cannot form such a broad-based government in haste. There are a couple of riders. He must first be allowed to implement the seven point understanding that he has signed with UCPN (Maoist) Chairman Prachanda who holds the key to a two-thirds majority in the CA. Secondly, as a powerful coalition partner, the Maoists status must be acknowledged by giving them either of the two portfolios of home affairs or defense as a matter of right (a likely prospect as of this writing). This means clear leverage for them to induct their combatants in the army, and other internal security apparatus.

Thirdly, the rest of the coalition partners must find a way out to sideline some of the radical constitutional demands of the Maoist politburo members. These include the ethnicized federal model, the Maoist form of government (without democratic opposition), the model of “committed judiciary” to be orchestrated by a committee in the legislature packed by the leading political party of the day, to mention a few. All these tasks look challenging to anybody who sees democratic constitution as the point of departure for the peace process.

There was one alternative scenario. It would have been possible for all democratic parties including the UML to negotiate with the Maoists on all these issues, had the Maoists been elected to the driving seat – a clear but tacit assurance to them that even if they concede to the essential democratic institutions and structures, they would be able to hold elections next spring under the new constitution as the leader of the caretaker government.

Had Prachanda been supported to head the government under this condition, he would have been able to concede some of the democratic demands more assuredly than what Jhalnath Khanal has unsuccessfully tried to do for the Maoists. With little to show for in returns, there does not seem to be much logic for the Maoists to cooperate to design a democratic system that pushes them to the sidelines.

The situation is certainly wobbly. In the present scenario, there is little time to go for change in the leadership in the government, or look forward to some miracles to happen, so that the CA is able to give a new constitution to the country. The only remaining alternative is the likely possibility of the Maoists joining the government and compromising with them on a constitution within the limited time at hand. There is no viable alternative to the Maoists as well. The parties must listen to each other over the external forces – which have proved time and again, that they are not only incompetent, but, but also irrational and unreliable except for their vested interests.

It is encouraging that the Chairperson of the CA, Subhash C. Nembang has already forwarded all remaining contentious issues in the constitution making to the House Constitutional Committee. Along with these issues, the Chairperson has also forwarded the report of what has been described as Gaps and Laps Committee, and the minutes of the successful meetings of the high level political taskforce, that had been informally established to work on the strictly formal issues.

This referral has two important consequences. The first implication is that the contentious issues which the high level political taskforce had not been able to sort out will be sorted out by the Constitutional Committee itself, which is a bigger forum in terms of the representation of all political parties in the house. The committee also comprises of senior leaders of the house elected in 2008, who are most capable people to make constitution making forward. Another effect of the decision is acknowledgement of the fact that efforts at sorting out differences on constitutional positions must be done within the house itself, and not outside the house, through any informal machinery.

It was necessary to bring in the high level political taskforce working informally outside the formal structure of the house within the accountability system of the house. The high level taskforce members are also the members of the CA, and can complete the tasks they have been doing outside, within the house itself.

There is no reason why the taskforce should operate from outside – giving the impression that the house is only the rubber stamp of the powerful parties working from outside the house in consortium (often unchecked).

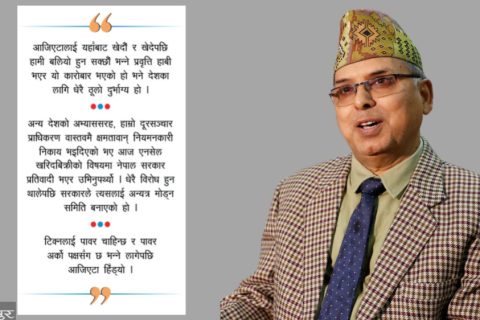

The president of the Constitutional Committee, Nilambar Acharya, who has voiced similar concerns over the past couple of months, has already welcomed the decision on similar grounds. With this decision, once again, the focus of the common people has moved from the high level political taskforce to the Constitutional Committee – the principal drafting organ of the house.

The job of the Constitutional Committee is not easy, even if the UCPN (Maoist) joins the government. The major issues, as stated above, are obviously those that relate with the form of government under the new constitution and the nature of federal system along with the number of and size of provinces. There must be efforts to move away from extreme positions, and develop on a convergence of opinion, on all these issues. It is very likely that in all these issues under discussion, the settlement that might be reached may fall below the level of what the constitutional experts have contemplated. It is important that the constitution making is completed, and a new process kicks off under the new statute.

As the word ‘compromise’ itself suggests, the purpose is to strike deal where political parties give up part of their demands to find agreement – often at variations from their original stands. After all, the CA is a divided house, at present representing 29 political parties, from the extreme left to the extreme right. There is no majority party in the house. In a situation like this, nobody can either prevail over others or ignore their risk. A two thirds majority to pass the new constitution is the constitutional rule. So a needful compromise will not be referred to as capitulation, as in a surrender of objectives or principles by the parties including the Maoists, in the process of constitutional negotiations.

Moreover, the work on an integrated first draft of the new constitution must start immediately based on the drafts submitted by the thematic committees of the CA. Although there are divergent proposals on these key issues, it should not prevent the Constitutional Committee from working on two or three parallel drafts, while the efforts at striking an integrated position on all these issues are under way.

The Constitutional Committee should also develop a mechanism within its framework which will be staffed by constitutional lawyers and thematic specialists outside the government framework.

These lawyers can also work together with the CA to revise the CA Rules, which must be properly adjusted if the constitution is to be adopted within the next three and half months. The formal processes inherent in the house rules do not allow for much time now to adopt the new constitution without readjusting some of their provisions. This also means further compromise with the participative mechanisms and time for the people to respond to the first integrated draft of the constitution.

(Adhikari is a constitutional expert).